Transition Design

A systems-based design response to food insecurity in Pittsburgh

Systems Thinking | Design Research | Data Visualization

Transition Design is a systems-based, trans-disciplinary approach that tackles complex "wicked" problems by targeting root causes and steering society toward sustainable, equitable futures through intentional, place-based transformation.

This seminar project, recognized as the "best outcome yet" by the founders of CMU's Transition Design Institute, examines Pittsburgh's food insecurity through multiple transition design perspectives, proposing a hyper-local integrated intervention plan to dismantle systemic barriers to food security.

Course: CMU MA in Design—Transition Design Seminar

Team: Lorin Anderberg, Diane Hu, Shama Patwardhan, Alisha Saxena

Tools: Miro, Figma Slides, Google Docs

Credits: Pexels, Canva + MidJourney, AI-Assisted Research/Copy Editing

Role: Research, Copywriting, Information Design, Data Visualization

Duration: 15 week sprint

Design Challenge

Food insecurity affects approximately 12.5% of Pittsburgh's population, disproportionately impacting vulnerable groups including low-income individuals, elderly residents, single parents, children, and marginalized communities who face the systemic inequalities of "food apartheid."

This project addresses Pittsburgh's food insecurity through a holistic understanding of these interconnected economic, transportation, and infrastructural challenges to develop equitable and sustainable solutions.

Timeline + Process

Throughout this seminar course, our team researched food insecurity in Pittsburgh through six Transition Design analysis exercises that enabled us to identify several key intervention points to drive systems-level change.

Each exercise was completed in 3 weeks and all team members split roles and responsibilities equally and independently before doing group analysis. I played a key role in the information design on our Miro board.

STEEP

Stakeholders

3 Weeks

Mapping Stakeholder

Relations

Multi-Level History

3 Weeks

Historical Analysis (Multi-Level Perspective Framework)

Futures I

3 Weeks

Developing Future Visions

(75 Years Ahead)

Futures II

3 Weeks

Establish & Dismantle for Future State

Interventions

3 Weeks

Designing Systems Interventions

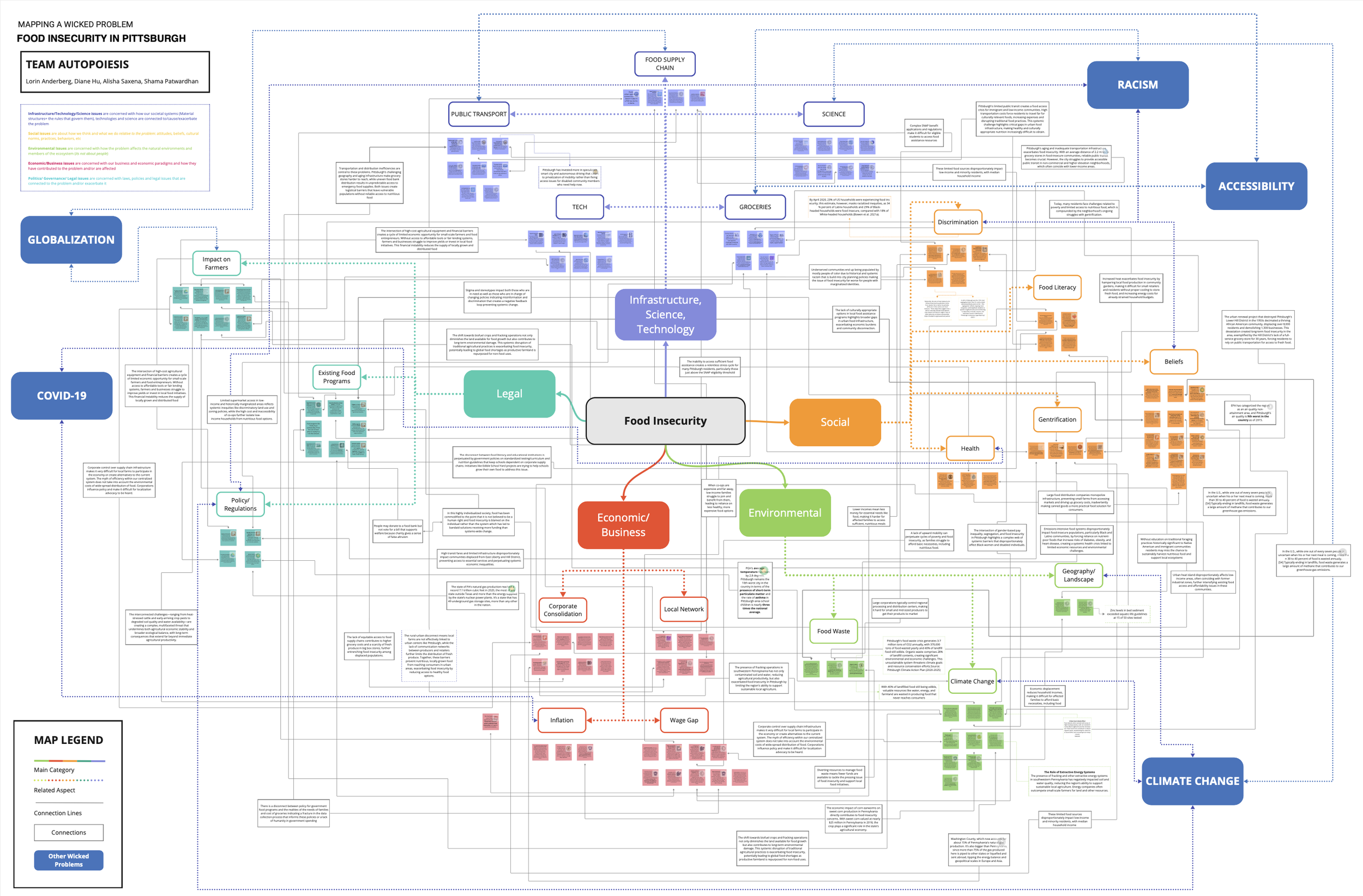

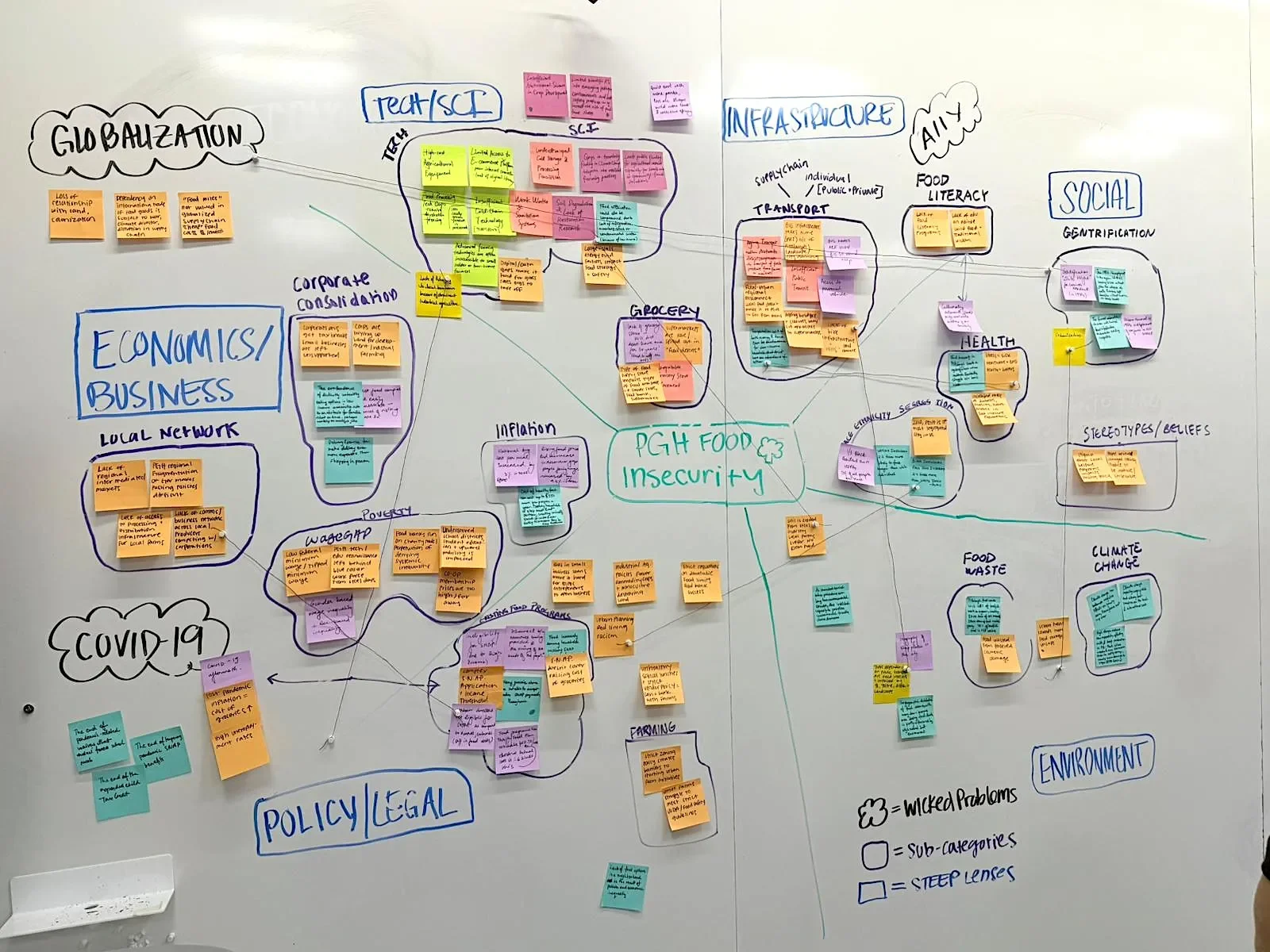

STEEP Analysis

Contextualizing food insecurity within socio-technical systems and identifying patterns, feedback loops, and leverage points. We began by situating food insecurity within the broader context of complex systems. Instead of looking at it in isolation, we explored how it’s entangled with other issues like poverty, urban infrastructure, social inequity, and environmental degradation.

From there, we built out a systems map to visualize these interconnections.

We identified stakeholders, institutions, and policies involved in the food ecosystem, and looked for patterns, feedback loops, and leverage points. We mapped out the socio-technical systems influencing access to food, such as transportation, zoning laws, grocery store locations, and community initiatives.

We quickly recognized that this wasn’t a problem with a simple solution. It was a classic example of a “wicked problem,” tangled in layers of historical, social, economic, and environmental factors. To begin unpacking it, we dove into extensive secondary research and started organizing our insights into five overarching categories: Infrastructure, Technology and Science; Economics and Business; Policy and Legal; Social; and Environmental. This framework helped us make sense of the interconnected nature of the problem.

We examined how factors such as outdated infrastructure and lack of technological access make it harder for communities to access fresh, healthy food. We explored how economic systems and business practices can either reinforce or help alleviate food insecurity. And we also considered the impact of social inequities and environmental challenges. By mapping these interdependent systems, we aimed to identify leverage points where thoughtful, long-term interventions could really make a difference, tailored specifically to Pittsburgh’s context.

Some key takeaways we carried forward from our research were the need to strengthen local food infrastructure, support small-scale producers through technology and policy reform, and address the digital divide that limits access to food systems. We also realized that long-term change requires shifting economic incentives and enabling community-driven food networks. These insights helped us identify leverage points for systemic intervention. Pittsburgh's food insecurity is fundamentally a problem of power

and control, where corporate consolidation and fragmented governance prevent communities from accessing their basic right to nourishment. The current system prioritizes profit over people, forcing vulnerable communities into cycles of stress and poor health while severing their connections to culturally relevant foods and local food sovereignty. Solving this crisis requires recognizing that food insecurity is a political issue demanding systemic change to restore community autonomy over food systems.

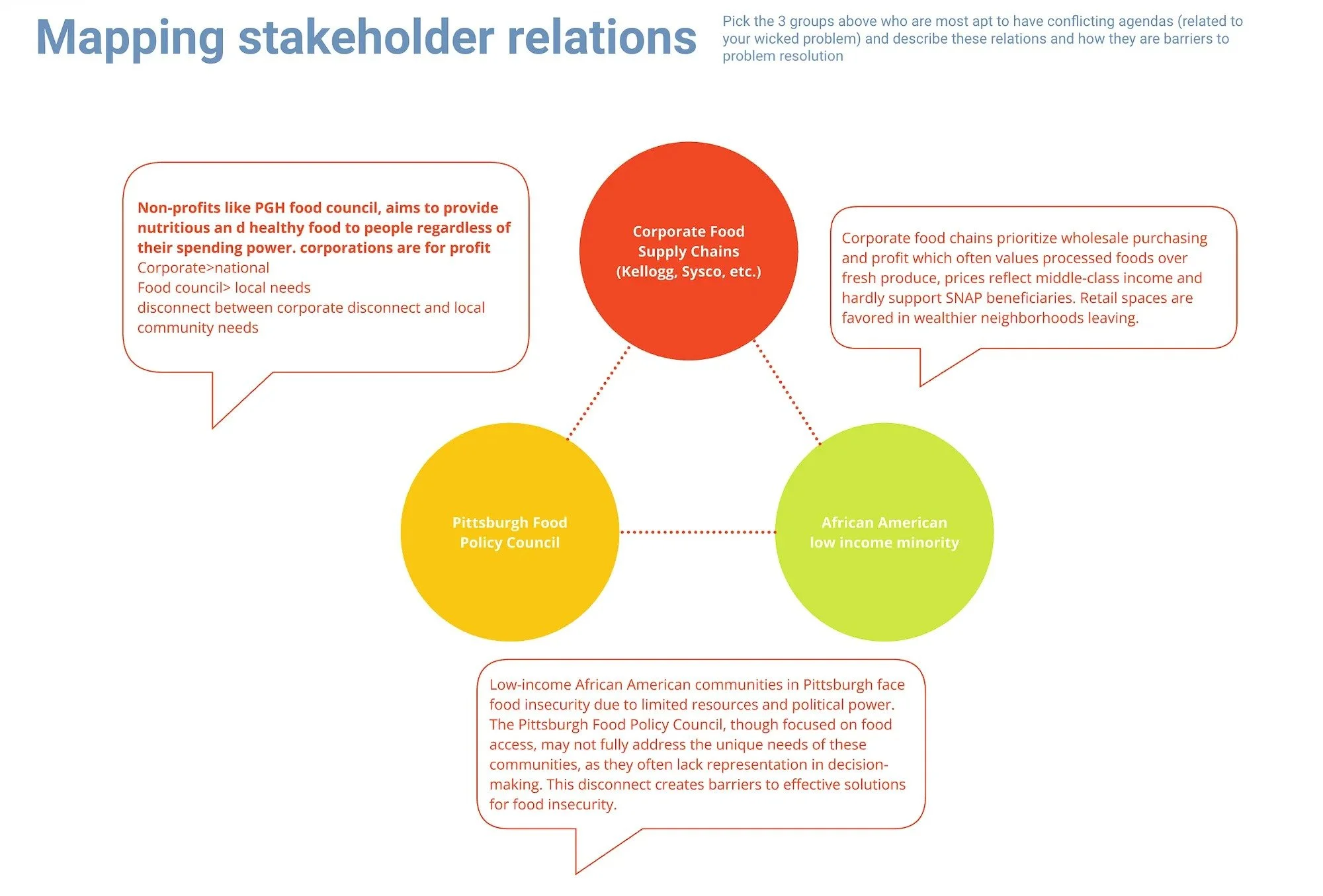

Stakeholder Analysis

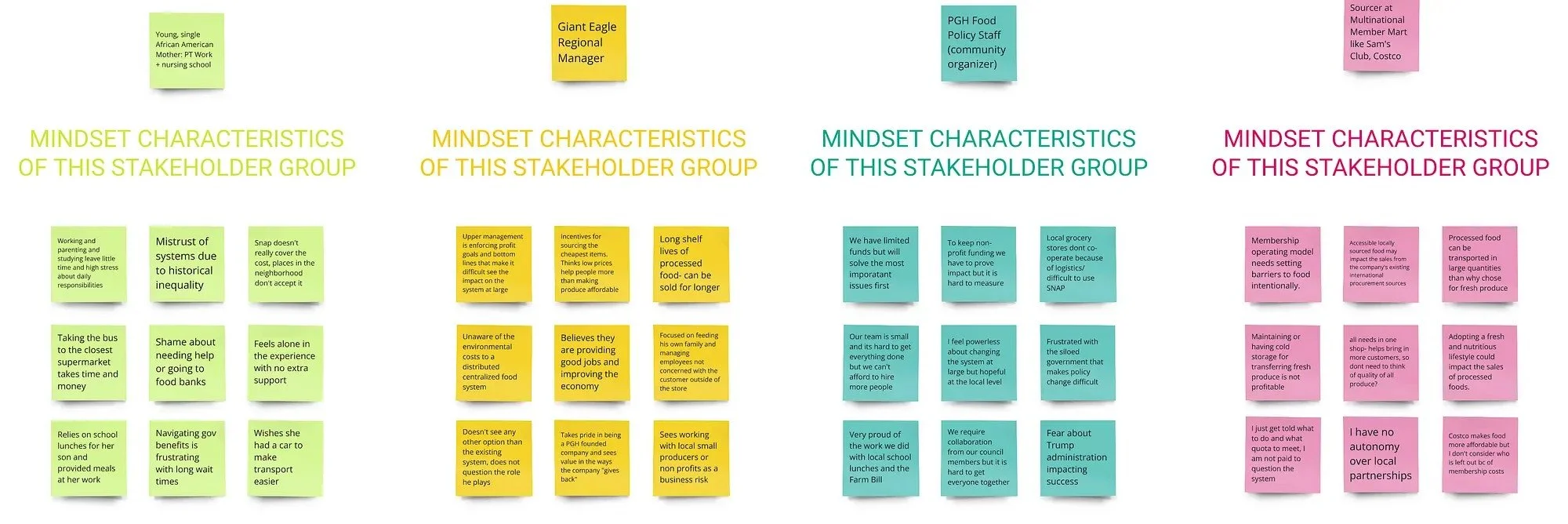

Mapping Pittsburgh’s food system through the lens of visible, hidden, and invisible power. Pittsburgh's food insecurity reflects deep systemic inequality where those with the least power (low-income families, elderly residents, and local farmers) struggle for basic necessities while corporations, developers, and policymakers wield significant influence over food systems, often benefiting from maintaining the status quo.

To create real change, we must understand these competing forces between the powerless, the powerful, and those maintaining current systems to identify intervention points and forge alliances that can disrupt the cycles sustaining food insecurity. We used the the Power Cube Framework to map key stakeholder groups in Pittsburgh’s food insecurity landscape which reveals a complex web of power dynamic.

The Marginalized Majority Low-income African American and Latinx communities, elderly and disabled residents, and local farmers face transportation barriers, financial strain, inadequate government programs, and corporate consolidation that pushes small producers out of distribution channels.

The Institutional Bystanders Powerful institutions like universities (CMU, Duquesne), tech companies (Google, Duolingo), and healthcare systems (UPMC) have resources to support local food systems but remain largely disconnected from food justice issues, focusing instead on profit and institutional expansion.

The Change Catalysts City planners, policymakers, transit agencies, and academic researchers possess unique leverage to drive systemic change through zoning reforms, improved transportation access, data-driven solutions, and coordinated action that can transform temporary assistance into lasting structural solutions.

The System Sustainers Major supermarket chains, real estate developers, fast food outlets, and low-wage employers profit from maintaining food insecurity through rigid supply chains that exclude local producers, neighborhood gentrification, processed food monopolies in food deserts, and dependence on financially unstable workforces.

The analysis examined stakeholder mindsets from a young African American mother facing transportation barriers to corporate executives focused on profit margins, revealing that systemic food system change requires addressing not just logistics but deeply held beliefs and institutional incentives. By understanding conflicting perspectives from personal frustration with government benefits to corporate operational pressures, the research shows that transformation demands tackling both structural barriers and underlying mindsets. This stakeholder analysis using the Power Cube Framework revealed the complex interplay of visible, hidden, and invisible power dynamics among key players in Pittsburgh's food system, from policymakers operating in constrained middle spaces to

corporations wielding economic influence to community members possessing the power of lived experience. The analysis highlighted that addressing food insecurity requires recognizing how different forms of power often conflict but can be strategically leveraged toward common goals. For example, framing local sourcing policies as economic incentives for corporations or building grassroots coalitions to demonstrate public support for policy changes. These insights will inform more targeted and comprehensive strategies that consider all stakeholder interests and influences, ensuring efforts to combat food insecurity are inclusive, effective, and responsive to community needs while acknowledging the ongoing need for stakeholder assessment throughout the project lifecycle.

Mapping Stakeholders on a Power Spectrum Key stakeholders were selected to represent different ends of the power spectrum and analyzed using the Power Cube Framework to identify opposing needs, values, and power dynamics that exacerbate food insecurity.

Power Imbalance and System Challenges Despite being most affected by food insecurity, the single Black mother has the least power to influence change, while the program manager's advocacy efforts are limited by corporate hidden power, highlighting the need for comprehensive strategies that address all levels of power dynamics in the food system.

Pittsburgh Food Policy Council Program Manager Wields visible power through policy influence, advocacy, and mobilizing stakeholders for change, but effectiveness is constrained by hidden and invisible power structures within the food system.

Giant Eagle Corporation Exercises hidden power by controlling pricing strategies, product offerings, and store locations in ways that significantly shape the food landscape and can either exacerbate or alleviate food insecurity.

Single Black Mother Experiences invisible power through systemic inequalities, racial and economic disparities, and cultural norms shaped by historical marginalization that limit her access to resources and full participation in the food system.

Historical Analysis

Tracing the roots of food insecurity through Pittsburgh’s industrial, racial, and urban development history using the MLP framework. Wicked problems like food insecurity cannot be fully understood, or effectively addressed, without considering their historical roots. The conditions we see today are the result of long-term, intertwined processes shaped by economic systems, political decisions, cultural shifts, and power dynamics that have unfolded over centuries.

The lens through which we view both history and a wicked problem determines what we see; a narrow focus on immediate conditions may obscure the deeper systemic forces at play. While a broader, more nuanced perspective reveals critical insights about how the problem evolved and where meaningful interventions might emerge. For transition designers, this means casting a wide net and engaging with historical, social, and economic contexts to design sustainable, justice-oriented solutions.

Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) Framework The MLP framework maps Pittsburgh's food insecurity across three interconnected levels to understand systemic change and identify opportunities for transformation rooted in historical racial injustices and industrial capitalism.

Landscape level: Broad societal forces like racialized economic policies, industrial shifts, and environmental change

Regime level: Dominant institutions, infrastructures, and policies that sustain food distribution while reinforcing structural inequalities

Niche level: Grassroots movements, community-led food initiatives, and alternative models challenging the dominant system

The Landscape Level Historical Timeline of Impact

Early 1900s: Steel industry boom displaced agricultural land and polluted environment; Great Depression and redlining deepened food insecurity in historically Black neighborhoods

Post-World War II: Suburbanization drew resources from urban cores

1970s-80s: Deindustrialization caused job losses and emergence of food deserts

1990s: Industrial agriculture rise and welfare reforms further limited healthy food access

2000s-Present: Great Recession, COVID-19, rising costs, and climate change exacerbated existing inequities

The Niche Level Community-led initiatives and emerging innovations offer promising alternatives to Pittsburgh's dominant food system through grassroots solutions that address access gaps and build resilience.

Current Community Innovations

Direct Access Solutions: Urban agriculture projects, mobile markets, food co-ops, and food rescue programs reduce waste while redirecting surplus to those in need

Regional Food Networks: Local food hubs and CSA models strengthen food economies and foster resilience against supply chain disruptions

Policy Advocacy: Grassroots efforts push for zoning reforms and universal free school meals, demonstrating scaling potential

Historical Grassroots Responses

Early Settlement: King's Garden addressed unreliable food supplies during settlement periods

Great Depression: Houses of Hospitality provided food and essentials, while informal economies like speakeasies emerged in working-class neighborhoods

Cultural Resilience: Soul food traditions offered nourishment and cultural strength for Black communities facing systemic food access inequities

Mid-Century Movement Building

Institutional Development: Original Farmer's Market (1919) and CSA programs reconnected residents with local food sources

Advocacy Organizations: Just Harvest and Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank tackled hunger through direct relief, education, and policy advocacy

Revolutionary Models: Black Panther Party's Free Lunch Program and Universal Basic Income efforts represented broader community-driven strategies

Recent Policy and Program Innovations

Funding Initiatives: Food Justice Fund Grassroots Grants Program ($1.5 million launching March 2025) and Community Food Solutions grants support local projects

Technology Solutions: 412 Food Rescue uses technology to optimize food distribution since 2015

Institutional Support: Pittsburgh Food Policy Council and CDBG Program promote urban agriculture and food accessibility

The Regime Level Pittsburgh's dominant food system relies on large grocery chains, centralized supply networks, and federal assistance programs that often fail low-income communities through profit-driven decisions and structural barriers.

Current System Characteristics

Corporate Control: Supermarkets prioritize profit over community access, leaving urban neighborhoods with limited fresh food options

Policy Barriers: Zoning laws and public health policies create obstacles to local food solutions

Infrastructure Limitations: Car-dependent design and social stigma around food assistance restrict access

Historical Regime Formation

Colonial Disruption: Indigenous sustainable food systems were destroyed by colonization and resource depletion

Industrial Impact: Steel industry displaced agricultural land, polluted environment, and prioritized manufacturing over food security

Systemic Racism: Slavery, redlining, and discriminatory policies excluded Black communities from land ownership and healthy food access, creating food deserts

Structural Reinforcement

Economic Shocks: Great Depression and deindustrialization drove unemployment, poverty, and grocery store closures in urban areas

Urban Planning Failures: Car-centric development and corporate supply chain control further limited food options

Climate Pressures: Extreme weather and urban heat islands increasingly threaten local food production and crop yields

Emerging Alternatives Community gardens, urban farming, and AgTech innovations provide grassroots solutions that strengthen food networks and offer education and economic development opportunities.

Conclusion: Pittsburgh's food insecurity crisis is deeply rooted in over 150 years of systemic patterns from industrial displacement of local food systems and racist urban planning that created food deserts, to climate change now exacerbating vulnerabilities in the city's most marginalized communities. While grassroots innovations like urban agriculture, mobile markets, and community fridges offer immediate relief and build on long traditions of mutual aid, lasting change requires addressing the slow-moving structural forces including corporate monopolies, car-centric infrastructure, and discriminatory policies that continue to maintain food inequities.

Imagining Futures

Envisioning a 75-year roadmap toward food sovereignty through community wealth building, mutual aid, and regenerative practices. We envisioned what Pittsburgh could look like in 2100 through our Living Land Vision: a future where food systems are rooted in mutual care, regenerative practices, and local abundance. This transition design exercise explores Pittsburgh's food insecurity through the lens of alternative economic models rooted in Indigenous practices of reciprocity, mutual aid, and collective stewardship that have long resisted extraction and prioritized community well-being over profit.

Drawing from philosophies like the Haudenosaunee Seven Generations Principle, Andean Pachakuti, and Buen Vivir, alongside models such as Community Wealth Building and the solidarity economy, the work envisions a future where food systems are decentralized and rooted in local stewardship rather than corporate dominance.

The name Living Land Vision reflects the deep, inherent connection between people, the earth, and sustainable, regenerative practices. It evokes an image of a flourishing, interconnected ecosystem. The word “Vision” captures the aspirational nature of the future we seek to create, while remaining open enough to inspire action across diverse communities. This language invites participation and emphasizes the holistic health of both people and the planet, while rejecting narratives of scarcity and profit-driven exploitation. By framing this future as living and nurturing, we shift the conversation toward abundance, interdependence, and shared responsibility, ensuring that no one is left behind in the vision we are building.

The different levels at which the vision works are: the household level which focuses on sustainable living practices, where families grow their own food and participate in community food-sharing networks. The neighborhood level emphasizes local food sovereignty, with cooperative farming and shared resources. At the city level, the vision calls for systemic change, including policy support for sustainable agriculture and green infrastructure. Finally, the planetary level stresses the need for regenerative environmental practices, ensuring ecological health on a global scale. From this aspirational future, we worked backward to build the Roots to Resilience Roadmap, identifying tangible interventions and milestones across decades.

A Household Rooted in Abundance

In every home, food is no longer a commodity but a birthright. Our pantries are full, not out of fear of scarcity but because our neighborhoods operate as one living system, ensuring that fresh, culturally relevant food is always available. Every household, whether an apartment or a standalone home, cultivates its own garden, a living extension of the family’s heritage and nutrition. Vertical indoor gardens hum with life, AI-assisted hydroponic systems adjusting in real time to each person’s dietary needs. Solar panels power our homes, organic waste nourishes communal green spaces, and clean energy circulates freely. The idea of a grocery bill is foreign to us; instead, our food flows through

a network of local abundance. “When I prepare a meal, I know that each ingredient was delivered through our neighborhood’s mobile food network and grown in harmony with the land, tended by hands that see food not as a product, but as a sacred trust.”

A Neighborhood Rooted in Reciprocity

Step outside, and you enter a neighborhood built on care. Children grow up understanding that their well-being is tied to the well-being of those around them. Community elders, once isolated in outdated systems of care, now hold places of honor, tending to gardens, mentoring youth, and sharing knowledge. The old model of transactional labor has been replaced by time banking and mutual credit systems. A few hours spent tending to the communal orchard might be exchanged for a lovingly prepared meal, a language lesson, or a childcare shift. Fresh markets and food hubs are interwoven into daily life, places where relationships flourish alongside the produce. Made-to-order food trucks, powered by the community’s harvest, roam the streets, not as businesses but as extensions of our shared table. Every evening, families walk together, tending to shared gardens, deepening their connection to both the land and each other. The burdens of modern life like caregiving, meal preparation, household labor are shared, not shouldered alone. In this way, we have redefined wealth, measuring it not in dollars, but in the strength of our relationships.

A Vision of Transformed Food Systems

Integrated Systems of Care Education and medicine are deeply intertwined with food sovereignty as schools teach sustainable living practices, hospitals operate as wellness centers using food as medicine, and global farm-to-institution programs connect regional farms with schools and hospitals worldwide through carbon-neutral, circular economy models.

A New Model of Prosperity In this reimagined world, Pittsburgh stands as the first Zero Hunger city and a global leader in community-driven food innovation, where wealth is measured not in profits but in the strength of relationships, soil health, and regional resilience. This serves as a model proving that when we choose systems rooted in reciprocity rather than exploitation, abundance and care can flourish for all.

Pittsburgh: From Steel to Food Sovereignty Step into a world where Pittsburgh has become a beacon of ecological and social restoration, leading a global transformation rooted in food sovereignty and regenerative practices. Once a city of industrial steel and economic hardship, Pittsburgh now thrives with cooperative housing and food villages where residents contribute through stewarding food forests, working in community kitchens, and developing collective innovations, while streets bloom with fruit trees and rooftops burst with edible gardens under Indigenous-led regenerative agriculture guidance.

Regional and Global Networks This local transformation extends across the region and planet, where decentralized AI-powered food networks eliminate waste by seamlessly redistributing surplus, farmers exchange climate-resilient knowledge across borders, and therapeutic gardens alongside biodiversity corridors create vibrant ecosystems where fresh produce flows freely as a common good.

Understanding the Transition to Food Sovereignty

To transform Pittsburgh's food system, we used Transition Design to create a roadmap that dismantles harmful structures (like distant corporate grocery stores and discriminatory policies), sustains what works (community co-ops, urban agriculture, safety net programs), and innovates new solutions. Our strategy moves from raising awareness about food apartheid as systemic inequality, to shifting cultural attitudes that remove stigma around food assistance, to building community-led food systems that replace corporate control with local ownership.

The transformation timeline progresses from immediate awareness campaigns, to medium-term policy changes that require neighborhoods to participate in local food systems, to long-term community wealth-building where co-ops and community-owned resources create resilient local economies that benefit residents rather than external corporations.

Emerging Ideas: Igniting the Transition

Mobile Markets to Doorstep Delivery Innovative practices like mobile markets, urban agriculture technology, and food rescue programs are reshaping Pittsburgh's food access. The evolution moves from expanding mobile markets that bring fresh produce to underserved neighborhoods (despite challenges like long lines and limited hours), to doorstep delivery programs that eliminate travel barriers for disabled, elderly. It includes transportation-limited residents to ultimately decentralized local food systems where communities rely on local farms and urban gardens rather than traditional grocery stores for consistent, sustainable food access.

Global Models to Local Innovation International examples like Europe's zero-waste aquaponics, Indigenous food sovereignty initiatives, pay-what-you-can cafés, and community-run grocery stores provide blueprints for Pittsburgh's transformation. The pathway progresses from returning land stewardship to Indigenous communities to preserve traditional foodways and sustainable practices, to forming ethical alliances between Indigenous knowledge and technology creating closed-loop regional food hubs. Eventually leading to to conservation-focused food production where aquaponics and vertical farming restore ecosystems while producing food sustainably and protecting cultural heritage.

Conclusion: From Vision to Reality

The Living Land Vision offers an urgent, achievable transformation from corporate-dominated food systems to community-driven alternatives rooted in Cosmopolitan Localism (locally rooted economies with global solidarity), Commoning (shared stewardship of land and food), Mutual Aid (collective care over charity), Pluriversality (honoring diverse wisdom traditions), and human needs-centered prosperity rather than profit-driven growth.

Transition Design provides the roadmap by dismantling corporate control and systemic inequalities while expanding localized food systems, urban agriculture, and cooperative economies. Through strategic planning from vision to implementation, Pittsburgh can cultivate a reality where food sovereignty becomes a birthright; proving that a just, community-based future is not only possible but necessary, and the seeds for transformation have already been planted.

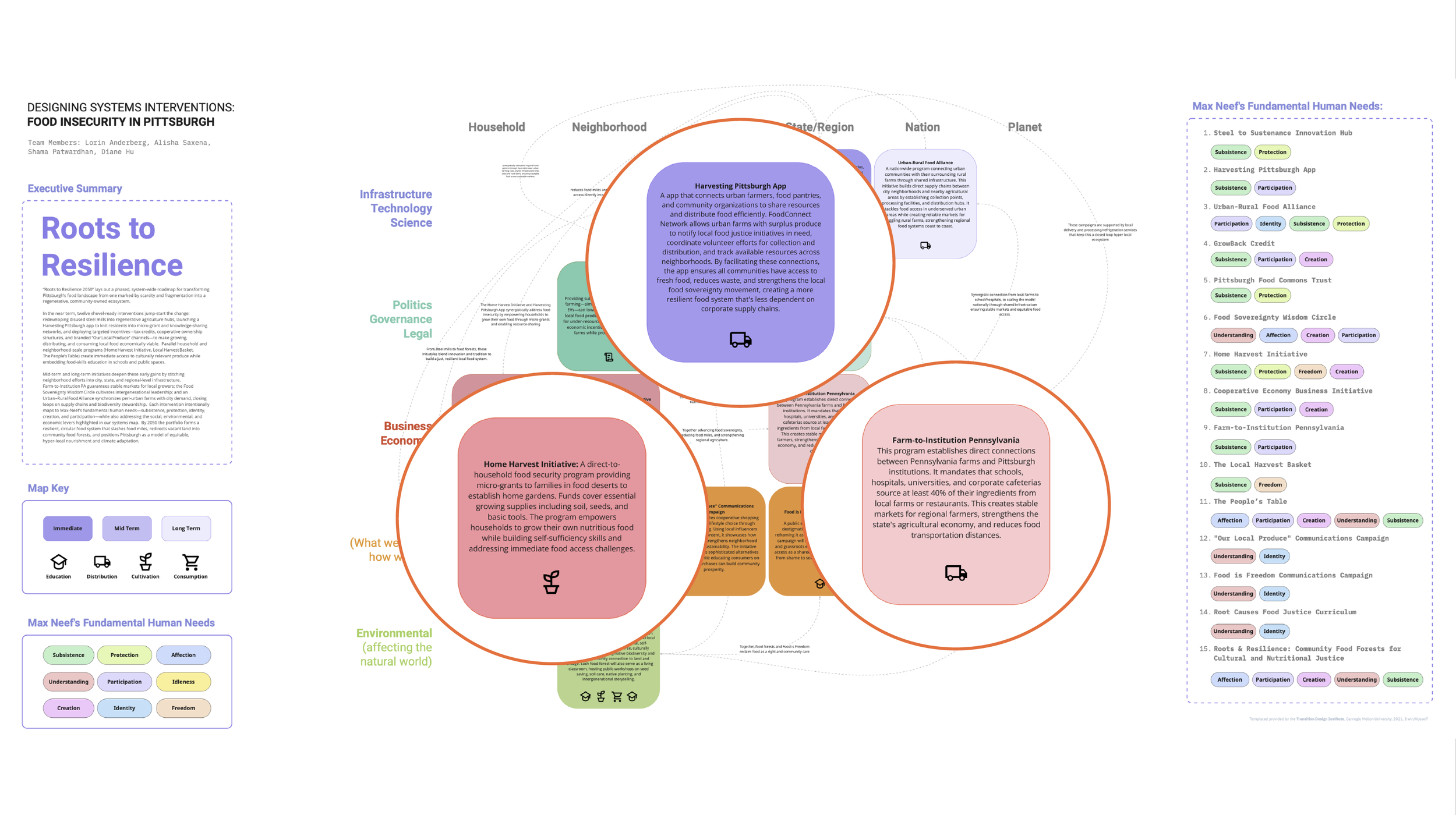

Systems Intervention

Outlining concrete, phased interventions to transition Pittsburgh’s food system from extraction to community stewardship. This transition design exercise explores Pittsburgh's food insecurity through the lens of alternative economic models rooted in Indigenous practices of reciprocity, mutual aid, and collective stewardship that have long resisted extraction and prioritized community well-being over profit.

Drawing from philosophies like the Haudenosaunee Seven Generations Principle, Andean Pachakuti, and Buen Vivir, alongside models such as Community Wealth Building and the solidarity economy, the work envisions a future where food systems are decentralized and rooted in local stewardship rather than corporate dominance. This project seeks to dismantle exploitative structures and build resilient food systems where access to nutritious food becomes a shared right rather than a privilege.

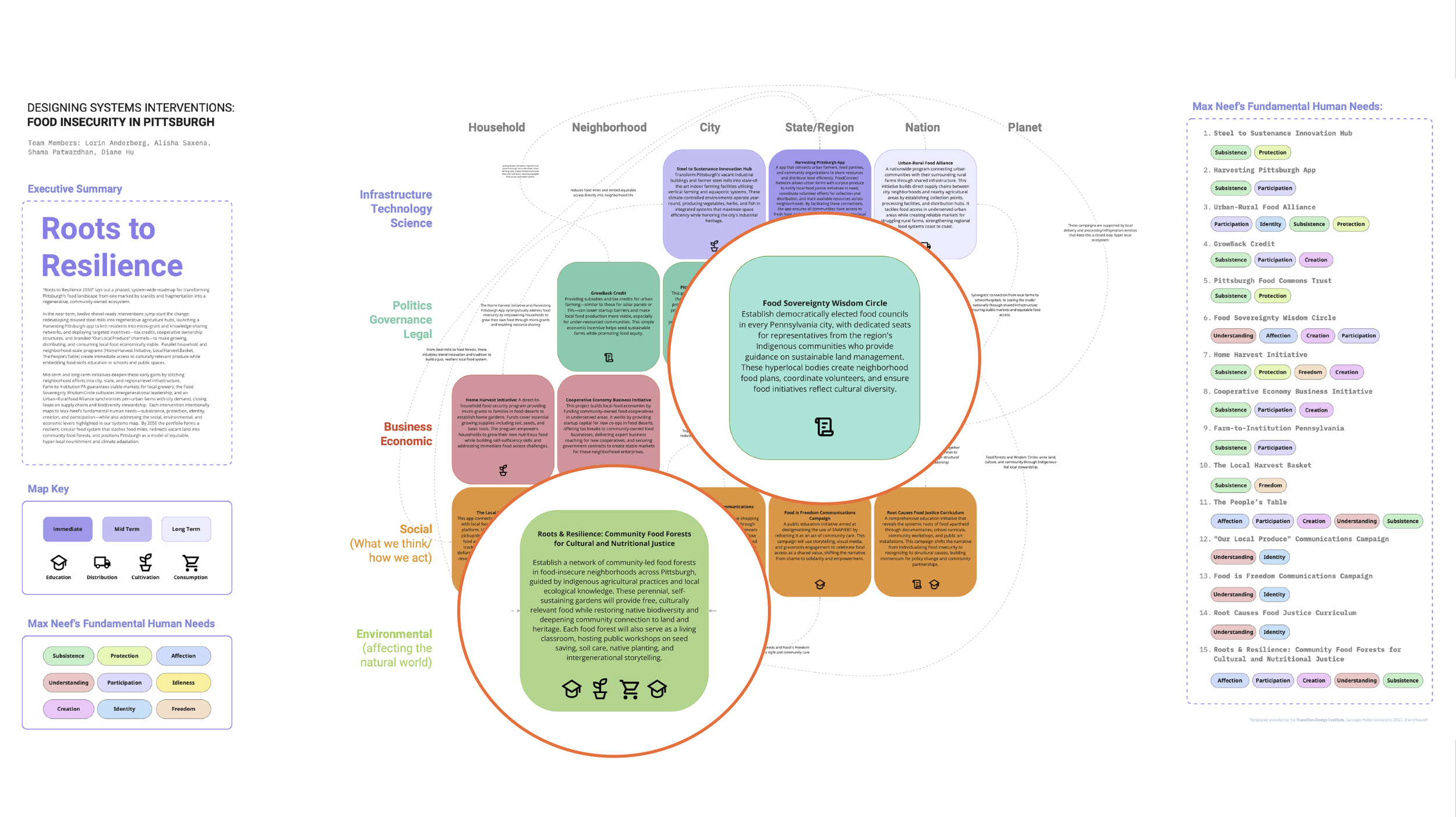

“Roots to Resilience 2050”

lays out a phased, system‑wide roadmap for transforming Pittsburgh’s food landscape from one marked by scarcity and fragmentation into a regenerative, community‑owned ecosystem.

In the near term, twelve shovel‑ready interventions jump‑start the change: redeveloping disused steel mills into regenerative agriculture hubs, launching a Harvesting Pittsburgh app to connect residents with micro‑grant and knowledge‑sharing networks. Then deploying targeted incentives like tax credits, cooperative ownership structures, and branded “Our Local Produce” channels to make growing, distributing, and consuming local food economically viable. Parallel household and neighborhood-scale programs (Home Harvest Initiative, Local Harvest Basket, The People’s Table) create immediate access to culturally relevant produce while embedding food‑skills education in schools and public spaces.

Mid‑term and long‑term initiatives deepen these early gains by stitching neighborhood efforts into city, state, and regional‑level infrastructure. Farm‑to‑Institution PA guarantees stable markets for local growers; the Food Sovereignty Wisdom Circle cultivates intergenerational leadership; and an Urban–Rural Food Alliance synchronizes peri‑urban farms with city demand, closing loops on supply chains and biodiversity stewardship.

Each intervention intentionally maps to Max‑Neef’s fundamental human needs (subsistence, protection, identity, creation, and participation) while also addressing the social, environmental, and economic levers highlighted in our systems map. By 2050 the portfolio forms a resilient, circular food system that slashes food miles, redirects vacant land into community food forests, and positions Pittsburgh as a model of equitable, hyper‑local nourishment and climate adaptation.